AUG. 20, 2014

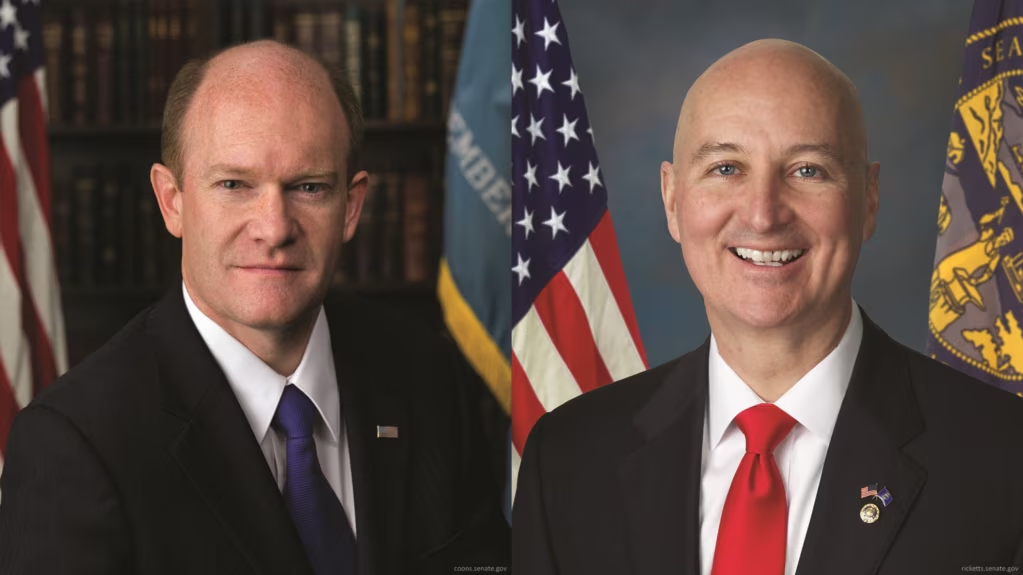

The documentary filmmaker Jocelyn Ford, left, and Zanta. Credit Sim Chi Yin for The New York Times

BEIJING — When the Tibetan farmer Zanta’s husband died, she was forced by local custom to move in with her in-laws, who forbade her son to attend school. Instead, she packed up and moved to Beijing, where she was helped by a relative from another lifetime.

That is the beginning of “Nowhere to Call Home,” a documentary by a foreign correspondent in Beijing, Jocelyn Ford, showing at the Museum of Modern Art this month. The film follows Zanta (who, like many Tibetans, goes by one name) here and in her hometown, where she confronts her father-in-law. Along the way, it becomes clear that the relative from another lifetime is Ms. Ford, who breaks the traditional wall between journalist and subject by becoming a friend.

The film breaks down the sometimes romantic Shangri-La view that Westerners have of Tibet, showing it to be a place with many hidebound traditions, especially discrimination against women. It also offers a shocking portrait of the outright racism that Zanta and other Tibetans face in Chinese parts of the country. And it shows how many members of minorities lack even basic education: Zanta’s sisters are illiterate, unable to count their change in the market or recognize the numbers on a cellphone. But maybe most surprising is that Ms. Ford has been quietly showing the film in China itself, eliciting admiration and unease that such a penetrating film was made by a foreigner.

The documentary filmmaker Jocelyn Ford directed “Nowhere to Call Home,” for which she befriended and shot footage of the Tibetan migrant Zanta at her home on Beijing’s outskirts and around the city. Credit Sim Chi Yin for The New York Times

“This film makes us question how we deal with people like this,” said Shi Peng, a reporter at the government news agency, Xinhua, where a screening was arranged this summer. “Do we help them enough?”

Mr. Shi said he was stunned by the inequality Tibetan women face. Zanta’s father-in-law is a violent tyrant, who treats her like his property. Zanta’s family is bullied in the village, because there are no sons, and her father is too old to fight.

In Chinese popular culture, Tibet, a population vacation destination for ethnic (or Han) Chinese, is seen as unspoiled, and Tibetans are often portrayed as simple people at one with nature, much as Native Americans were depicted in earlier decades in the United States. Despite the booming tourism, however, visitors rarely see the reality of daily life in Tibet.

Shen Ye, a 30-year-old who works at an independent record label in Beijing, said that a few years ago she spent eight months backpacking through Tibet. But a screening of Ms. Ford’s movie at a small club’s independent movie night here proved eye-opening.

“I lived in Tibet and didn’t know about it,” Ms. Shen said. “You just see propaganda. I never knew what their real lives were like.”