原文作者:Mark Galeotti /马克·加莱奥蒂

译者:白丁

原文标题

Russia’s Vladimir Putin at 70: Seven key moments that made him

原文链接

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-63117878

【原文注:马克·加莱奥蒂(Mark Galeotti)教授是一位学者和作家,他的著作包括《我们需要谈谈普京和即将到来的普京战争》。】

周五,弗拉基米尔·普京 (Vladimir Putin) 即将迎来 70 岁生日。这个发动了灾难性的乌克兰入侵的人是如何走上孤立的独裁者之路的?

他生命中的七个关键时刻塑造了他的思想,并解释了他与西方日益疏远的原因。

1964年,发现并投身柔道

年轻的弗拉基米尔出生在列宁格勒,一座因第二次世界大战中长达 872 天的围困而仍然伤痕累累的城市。

在学校里,普京是一个脾气暴躁和好斗的男孩——他最好的朋友回忆说,“他会和任何人打架”,因为“他没有恐惧” .

尽管如此,在一个街头帮派猖獗的城市里,一个身材瘦小但好斗的小男孩需要有一个优势。他在 12 岁时首先学习三宝,一种俄罗斯武术;然后是柔道。他意志坚定,严格自律,18岁时获得柔道黑带段位,并在全国青少年比赛中获得第三名。

当然,这已经被用作他精心策划的男子气概的一部分,但这也证实了他早期的信念,即在一个危险的世界里,你需要自信,但也要意识到,用他自己的话来说,当一场战斗无法避免时,“你必须先出手,并且出手力度要大到让对手爬不起来”。

1968年,到克格勃求职

总体而言,人们避免前往位于列宁格勒的克格勃政治警察总部所在地 Liteyny Prospekt 大街4号。在斯大林时代,有那么多人经过它的审讯室走进古拉格劳改营,以至于流传着这样一个苦涩的笑话:大家熟知的Bolshoi Dom,也就是“大房子”,是列宁格勒最高的建筑,因为从它的地下室就可以看到西伯利亚。

尽管如此,在他 16 岁的时候,普京还是走进了铺着红地毯的接待处,向桌子后面相当困惑的官员询问他该如何加入克格勃。他被告知他需要完成兵役或是获得学位。他于是追问哪个学位最好。

法律,他被告知。从那时起,普京就下定决心要攻读法律专业。之后他被正式招募。对于普京这个聪明的街头暴徒来说,克格勃是镇上最大的帮派,它甚至能为那些即使是与党没有关系的人提供安全保障和上升的机会。

这表明它同时也是一个普通人成为推动者和震荡者的机会——正如他自己在谈到他十几岁时看过的间谍片时所说的那样,“一个间谍可以决定成千上万人的命运”。

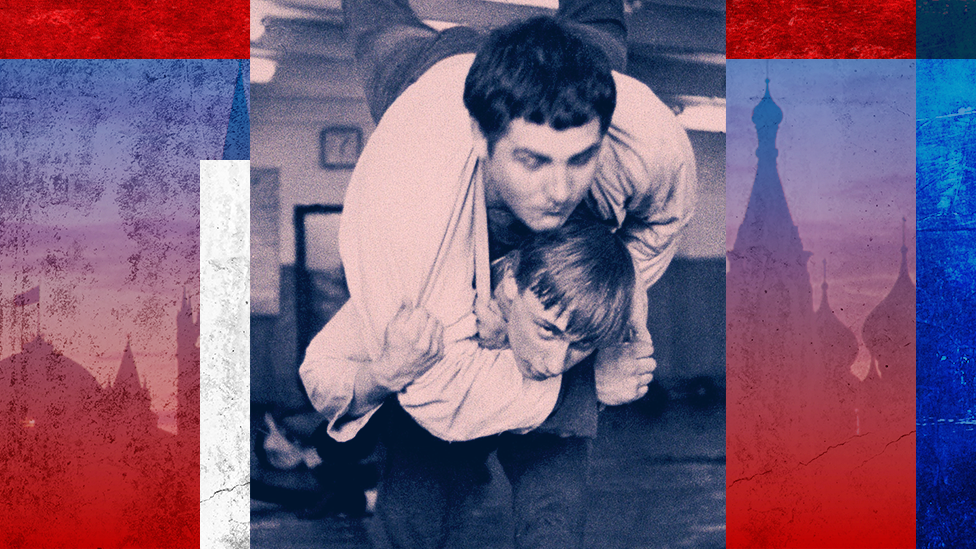

(图1 1971年与同学摔跤)

1989年,被骚乱造者包围

尽管充满希望,但普京的克格勃生涯从未真正起飞。他是一个实干的人,而不是怀有极高的抱负。尽管如此,他还是致力于学习德语,这使他在 1985 年被任命前往克格勃在(德国)德累斯顿的联络处。

在那里,他过上了舒适的侨民生活。但在 1989 年 11 月,东德政权以惊人的速度开始崩溃。

12 月 5 日,一群骚乱者包围了德累斯顿克格勃大楼。普京拼命打电话给最近的红军驻军请求保护,但他们无奈地回答:“没有莫斯科的命令,我们什么都做不了。莫斯科在保持沉默。”

普京从中学到了对中央政权突然崩溃的恐惧——并决心不再重复他认为是苏联领导人戈尔巴乔夫犯下的错误,即在面对反对派时没有迅速而坚定地做出反应。

1992 年,经理“石油换食品”计划

随着苏联解体,普京原本要离开克格勃,但很快就在这座现在改名为圣彼得堡的城市获得了一个为改革派新市长处理事务的职位。

经济正处于自由落体状态,普京负责管理一项试图帮助该市人民渡过难关的交易,用价值 1 亿美元(8800 万英镑)的石油和金属换取食物。

但是真实情况是,没有人看到任何食物。根据一项很快就被压制了的调查得知,普京、他的朋友和该市的黑帮成员将这笔钱款收入私囊。

在“狂野的 90 年代”,普京很快了解到政治影响力是一种可以货币化的商品,黑帮可以成为有用的盟友。当周围的人都在通过自己的职位获利时,为什么他不该同样这么做?

2008年,入侵格鲁吉亚

当普京在 2000 年成为俄罗斯总统时,他希望能够与西方建立积极的关系——但要按照他自己的条件,包括覆盖前苏联版图的势力范围。他很快变得失望,然后是愤怒,他认为西方正在积极地试图孤立和贬低俄罗斯。

当格鲁吉亚总统米哈伊尔·萨卡什维利(Mikheil Saakashvili)承诺说他的国家将加入北约时,普京看到了红色警号,而格鲁吉亚试图重新控制被俄罗斯支持的南奥塞梯(South Ossetia)分离地区的行动成为了惩罚的借口。

(图2 南奥塞梯妇人哀悼她的儿子)

五天之内,俄罗斯军队摧毁了格鲁吉亚军队,并在萨卡什维利(Saakashvili)强行实现了屈辱性质的和平。

西方被激怒了。但不到一年,美国总统奥巴马提出要“重置”与俄罗斯的关系,莫斯科甚至获得了举办 2018 年足球世界杯的奖励。

对普京来说,很明显武力带来公义——一个软弱和反复无常的西方虽然会恼怒和恫吓,但最终会在坚定的意志面前退缩。

2011-13年,莫斯科的抗议活动

一种普遍并且可信的看法是, 2011 年因议会选举被操纵而引发的抗议活动,是在普京宣布他将在 2012 年竞选连任时才被激起的。

抗议期间,莫斯科广场上挤满了抗议的人们。这场之后被称之为“博洛特纳亚抗议”的运动,是普京执政期间公众发出的最大的反对声音。

普京认为,这些集会是由华盛顿发起、鼓励和指挥的,并指责美国国务卿希拉里·克林顿个人。

对普京来说,这表明对手已经赤膊上阵,西方正在直接向他扑来,实际上,他现在正处于战争状态。

2020-21年,与 Covid 隔离

当 Covid-19 席卷全球时,普京进入了一种即使对于唯我独尊的独裁者来说也不同寻常的隔离状态,任何与他见面的人都要先被隔离两周,然后还要穿过一条充满杀菌紫外线和消毒剂喷雾的走廊。

在这段时间里,能够与普京面对面的盟友和顾问数量急剧减少,只剩下少数几个应声虫和鹰派伙伴。

面对更少的不同意见,甚至几乎不怎么看得到自己的国家,普京似乎已经“了解到”,他所有的假设都是正确的,他的所有偏见都是合理的。入侵乌克兰的种子已经播下了。

(2,172 words)

Russia’s Vladimir Putin at 70: Seven key moments that made him

-

Published

As Vladimir Putin nears his 70th birthday on Friday, how did he become the isolated autocrat who launched his disastrous invasion of Ukraine?

Seven pivotal moments in his life helped shape his thinking and explain his growing estrangement with the West.

Taking up judo, 1964

Born in a Leningrad still scarred by its 872-day siege in World War Two, young Vladimir was a surly and combative boy at school – his best friend recalled that “he could get into a fight with anyone” because “he had no fear”.

Nonetheless, a slight but scrappy young boy in a city overrun with street gangs needed an edge, and at the age of 12 he took up first sambo, a Russian martial art, and then judo. He was determined and disciplined, and by the time he was 18 had a judo black belt and third place in the national junior competition.

Of course, this has since been used as part of his carefully-curated macho persona, but it also confirmed his early belief that in a dangerous world, you need to be confident but also realise that, in his own words, when a fight is inevitable, “you must hit first, and hit so hard that your opponent will not rise to his feet”.

Asking the KGB for a job, 1968

On the whole, people avoided going to 4 Liteyny Prospekt, the KGB political police HQ in Leningrad. So many had passed through its interrogation cells to the gulag labour camps in the Stalin era that the bitter joke was that the so-called Bolshoi Dom, the “Big House”, was the tallest building in Leningrad, because one could see Siberia from its basement.

Nonetheless, when he was 16, Putin entered its red-carpeted reception and asked the rather bemused officer behind the desk how he could join. He was told that he needed to have completed military service or a degree, and so he even asked which degree was best.

Law, he was told – and from that point, Putin was determined to graduate in law, after which he was duly recruited. To Putin the street-smart bruiser, the KGB was the biggest gang in town, offering security and advancement even to someone with no Party connections.

But it also represented a chance to be a mover and shaker – as he himself said about the spy films he watched as a teenager, “one spy could decide the fate of thousands of people”.

Surrounded by a mob, 1989

For all his hopes, Putin’s KGB career never really took off. He was a solid worker, but no high flier. Nonetheless, he had applied himself to learning German, and this got him an appointment to the KGB’s liaison offices in Dresden in 1985.

There he settled into a comfortable expat life, but in November 1989, the East German regime began to collapse, with shocking speed.

On 5 December, a mob surrounded the Dresden KGB building. Putin desperately rang the nearest Red Army garrison to request protection, and they helplessly replied “we cannot do anything without orders from Moscow. And Moscow is silent.”

Putin learned to fear the sudden collapse of central power – and determined never to repeat what he felt was Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s mistake, not to respond with speed and determination when faced by opposition.

Brokering the ‘Oil for Food’ programme, 1992

Putin would later leave the KGB as the Soviet Union imploded, but soon secured a position as fixer for the reformist new mayor of what was now St Petersburg.

The economy was in freefall, and Putin was charged with managing a deal to try and help the city’s people get by, swapping $100m (£88m) worth of oil and metal for food.

In practice, no one saw any food, but according to an investigation, quickly suppressed, Putin, his friends and the city’s gangsters pocketed the money.

In the “wild 90s”, Putin quickly learned that political influence was a monetisable commodity, and gangsters could make useful allies. When everyone around him was profiting from their positions, why shouldn’t he?

Invading Georgia, 2008

When Putin became Russian president in 2000, he hoped to be able to build a positive relationship with the West – on his own terms, including a sphere of influence across the former Soviet Union. He soon became disappointed, then angry, believing the West was actively trying to isolate and demean Russia.

When Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili committed his country to joining Nato, Putin saw red and a Georgian attempt to regain control over the Russian-backed breakaway region of South Ossetia became an excuse for a punitive operation.

In five days, Russian forces shattered the Georgian military and forced a humiliating peace on Saakashvili.

The West was outraged, yet within a year, US president Barack Obama was offering to “reset” relations with Russia, and Moscow was even awarded the right to host the 2018 football World Cup.

To Putin, it was clear that might made right – and a weak and inconstant West would huff and puff, but ultimately back down in the face of a determined will.

Protests in Moscow, 2011-13

A widespread – and credible – belief that the 2011 parliamentary elections were rigged sparked protests that were only galvanised when Putin announced that he would be standing for re-election in 2012.

Known as the “Bolotnaya Protests” after the Moscow square that they filled, this represented the largest expression of public opposition yet under Putin.

His belief was that the rallies were initiated, encouraged and directed by Washington, blaming US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton personally.

To Putin, it was evidence that the gloves were off, and the West was coming directly for him, and that, in effect, he was now at war.

Isolating from Covid, 2020-21

When Covid-19 swept across the globe, Putin went into an isolation unusual even for personalistic autocrats, with anyone going to meet him being isolated for a fortnight under guard and then having to pass through a corridor bathed in germ-killing ultraviolet light and fogged in disinfectant.

In this time, the number of allies and advisers able to have face time with Putin shrank dramatically to a handful of yes-men and fellow hawks.

Exposed to fewer alternative opinions and scarcely even seeing his own country, Putin seems to have “learned” that all his assumptions were right and all his prejudices justified, and the seeds of the invasion of Ukraine were planted.

Professor Mark Galeotti is an academic and author, whose books include We Need To Talk About Putin and the forthcoming Putin’s Wars