August 2, 2017

The Lonely Crusade of China’s Human Rights Lawyers

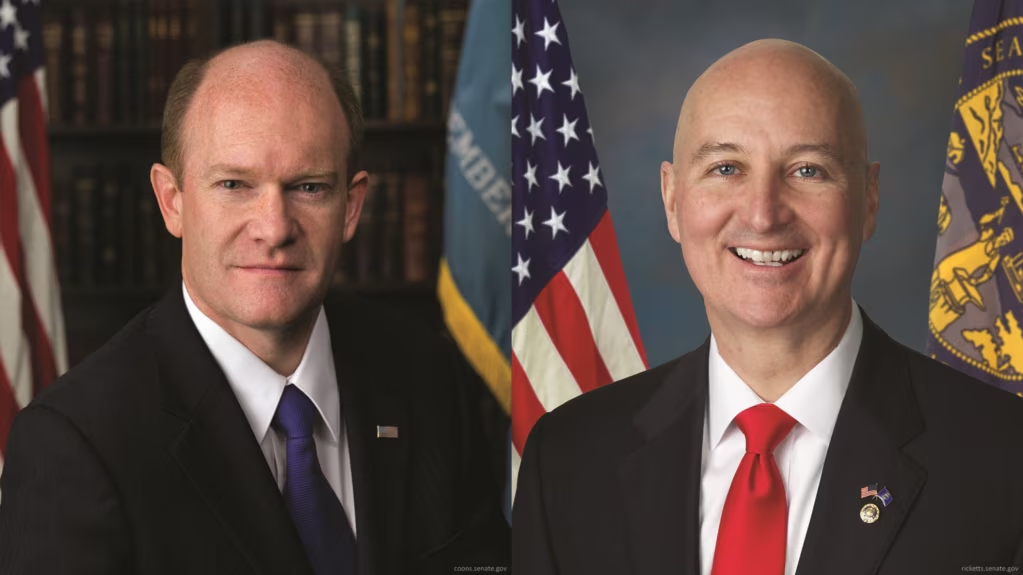

From left: Wang Qiaoling, whose husband, Li Heping, was detained during the 709 crackdown, and Li Wenzu, wife of Wang Quanzhang, with Wang Quanzhang’s parents, getting ready to protest in front of the prosecutor’s office in Beijing in June.

Giulia Marchi for The New York Times

In the years since the movement’s founding, rights defense lawyers have taken up causes including freedom of expression, labor rights, religious freedoms and advocacy for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people. Yet in every case, the lawyers face a common and elemental adversary: fear. Beyond beliefs or values, this is what unites the movement’s members. ‘‘I think you can probably go inside lots of law schools’’ in China ‘‘and speak to lots of students and find they have pretty liberal ideas,’’ Pils told me. ‘‘It makes sense to most people that law is better served by, for instance, an autonomous judiciary.’’ But that does not make them human rights lawyers, she says. ‘‘It’s really a question of, Can you withstand the pressure?’’

Under President Xi, that pressure has ratcheted up across Chinese civil society. As part of a far-reaching campaign to stamp out ‘‘foreign hostile forces,’’ the government has detained and deported foreign activists, denied medical care to detainees and revived the practice of forced televised confessions, a throwback to the days of internal party purges. The campaign has been justified by a host of new legislation granting the government a free hand over almost any matter deemed relevant to national security.

For lawyers who veer into sensitive areas of the law, the pressure is applied slowly; it begins with a simple invitation to tea from the police. What kinds of cases are you working on? an officer asks. Do you know what your colleague has been up to lately? How are your children finding their new teacher?

Often, the first meeting is enough to change a lawyer’s course. For those who continue, the pressure gradually escalates: frequent visits from the judicial bureau, being constantly followed and messages from government minders — ‘‘Be careful what you say at your meeting this morning’’ — that serve both to intimidate and to remind that someone is watching.

The pressure can be startlingly personal. In the on-and-off cycle of repression and relaxation, some minders treat their target to dinner one week, then interrogate him the next. Softening euphemisms abound: to have been ‘‘spoken to,’’ instead of threatened; ‘‘educated,’’ instead of disciplined. Somehow the fear and the constant threat of violence become normalized. ‘‘At first you’re scared just to talk to someone,’’ Pils says. ‘‘And then one day you’re used to the idea that you could be taken anytime.’’

For Liang, it was soon after accepting his first human rights case in 2008 that he came to the attention of the authorities. In 2010, he was prevented from attending a meeting for the first time. A European embassy in Beijing was holding a conference on rule of law, and the organizers invited Liang to speak. The morning of the event, two policemen knocked on his door. They stayed with him throughout the day, gave him lunch and then sent him home after the conference concluded. Since then, the harassment has been nearly constant, including intimidation from government thugs and raids targeting Liang’s office.

The most jarring incident came in August 2015, a month after the 709 arrests. Liang was with his wife and son at the Beijing airport, preparing to fly to New York for an exchange program at Columbia University. When the family was at customs, Liang was stopped and told that he was not allowed to travel. ‘‘They said I might endanger national security,’’ Liang says. He has been unable to leave the country since.

Before his travel ban, Liang opted to stay silent about the 709 crackdown. Having been granted a visa to the United States, he hoped to keep a low profile and so maintain his freedom to travel with his family. When that hope proved illusory, his calculus changed. ‘‘I decided, Well, I might as well go public,’’ he told me. He began to write articles under his own name and openly denounced the detentions as illegal. And yet Liang has also made his accommodations to the system. Faced with the same decision as his friend Xie Yanyi, Liang chose to sign the forms, make the promise, nod when told. Liang has rarely been detained for longer than 12 hours, a rare distinction among human rights lawyers.

As he sees it, minimizing confrontation is a matter of tactics. ‘‘I don’t deal with the police too hard,’’ he told me, as we rode the subway from the detention center back to central Tianjin. ‘‘The police press me to take a pledge to do something, I say O.K. Because for them, there’s no law. If they don’t act in accordance with the law, I don’t need to keep my pledge to them. I just need to do the things I think are right.’’

I asked Liang if he considered himself a brave man. He paused. ‘‘I think I’m not braver than the lawyers in the detention centers,’’ he said. ‘‘Sometimes I’m scared, and I still try to do the right thing, to defend sensitive cases and challenge the party in accordance with the law. But I have a family and parents, a wife and son. I need to protect myself sometimes.’’

We reached our station and shuffled up the stairs. Before reaching the top, Liang stopped and turned to me. ‘‘Do you know ‘The Catcher in the Rye’?’’ he asked. He began to paraphrase a passage: ‘‘An immature man wants to die nobly for a cause. A mature man wants to live humbly for one.’’ He gave a small smile and fidgeted with his jacket pocket. ‘‘I use these words to comfort myself sometimes.’’

In the aftermath of the 709 arrests, the police turned their attention to some of the wives and family members of the detained lawyers. The pressure became especially intense after two of the wives, Wang Qiaoling and Li Wenzu, began holding public demonstrations and pressing the government for answers. Together the women rallied the wives of the detained lawyers into an impromptu community, half support group and half protest movement.

While lawyers like Liang navigated the byzantine legal system, the wives became the public face of 709, leading small rallies and protests in Beijing, Tianjin and other cities. The wives traveled to the detention center in Tianjin with a nearly religious devotion. Each week, they took family and friends and posted photos online of their children frolicking on the beige linoleum floor of the prosecutor’s office, like snapshots from a dystopian family vacation.

I met Wang and Li in a wood-paneled coffee shop on a blistering summer afternoon, a little more than a week before the first anniversary of the crackdown. The worst part of their husbands’ sudden disappearance, they agreed, was trying to explain the situation to their young children. Li, whose husband was Liang’s friend Wang Quanzhang and whose son was 2½ when his father disappeared, tried at first to maintain a veneer of normalcy, telling her son that his father was on a business trip. But over the course of the year, as the family visited detention centers, police stations and lawyers, the boy came to realize that his father had been taken to prison. He asked his mother why.

‘‘I explained that he is a lawyer,’’ Li told me. ‘‘He has to help others. Because he helps others, he has been taken away by monsters.’’ Wang put her hand on Li’s back as she continued. ‘‘ ‘Why doesn’t he come back?’ my son asked. ‘Are there too many monsters?’ I said to him, ‘If you be good and grow strong, you can help your father fight the monsters.’ ’’ She paused and took a sip of tea. Li’s husband often came to Liang’s office to work, and the books he had left behind still cluttered Liang’s shelves — and as she spoke, Liang kept his eyes down, fiddling with a pen. ‘‘He asked if others are also helping fight the monsters,’’ Li said. ‘‘I told him, ‘Yes, many people.’ ’’

Yet despite their troubles, it was Xie’s wife, the women agreed, who was in the toughest position. She lived far outside the city, isolated from the other wives and sources of support. And only Yuan had a new baby to care for, a distinction that the authorities had employed as a powerful bargaining chip.

The police had offered Yuan a deal: If she would write a letter persuading her husband to confess, they would recommend a lighter sentence, and he would be allowed to see a photo of the baby. It was the only way, the police said, to reform Xie’s ‘‘poor attitude.’’ Liang warned her to resist. ‘‘They are trying to put psychological pressure on Mr. and Mrs. Xie,’’ he told me. ‘‘I think it would cause Mr. Xie to break down. As a man, seeing video of your baby when you’re not there — it would be too hard.’’ Yuan hesitated at first, desperate for any form of contact with her husband, but eventually she agreed. She became an active member of the wives’ group, traveling repeatedly to the detention center to demonstrate.

In the coffee shop, Wang and Li began planning for the coming anniversary of the crackdown. They had yet to decide what form their protest would take; they discussed the possibility of all the wives’ wearing red. ‘‘The red makes us feel better,’’ Wang said. ‘‘We want to show our optimism, so every time we go to Tianjin, we wear red.’’

As we got up to leave, Wang and Li pulled two short stacks of white printer paper from their purses and handed them to Liang. ‘‘Just in case,’’ Li said. Scrawled across the pages were handwritten power-of-attorney forms, naming Liang as the lawyer for both of them in the event that they were detained. Liang tucked the papers into his backpack without a word. The wives waved goodbye, then stepped out into the blazing sun arm in arm.