Xi Jinping is ‘an idiot’ and ‘my biggest promoter’

— writer Liao Yiwu

白痴习近平是我“最大的推销商”——作家廖亦武

中文在后面

Recorded by Jonathan Landreth is a Brooklyn-based writer and editor who started reporting from China in 1997

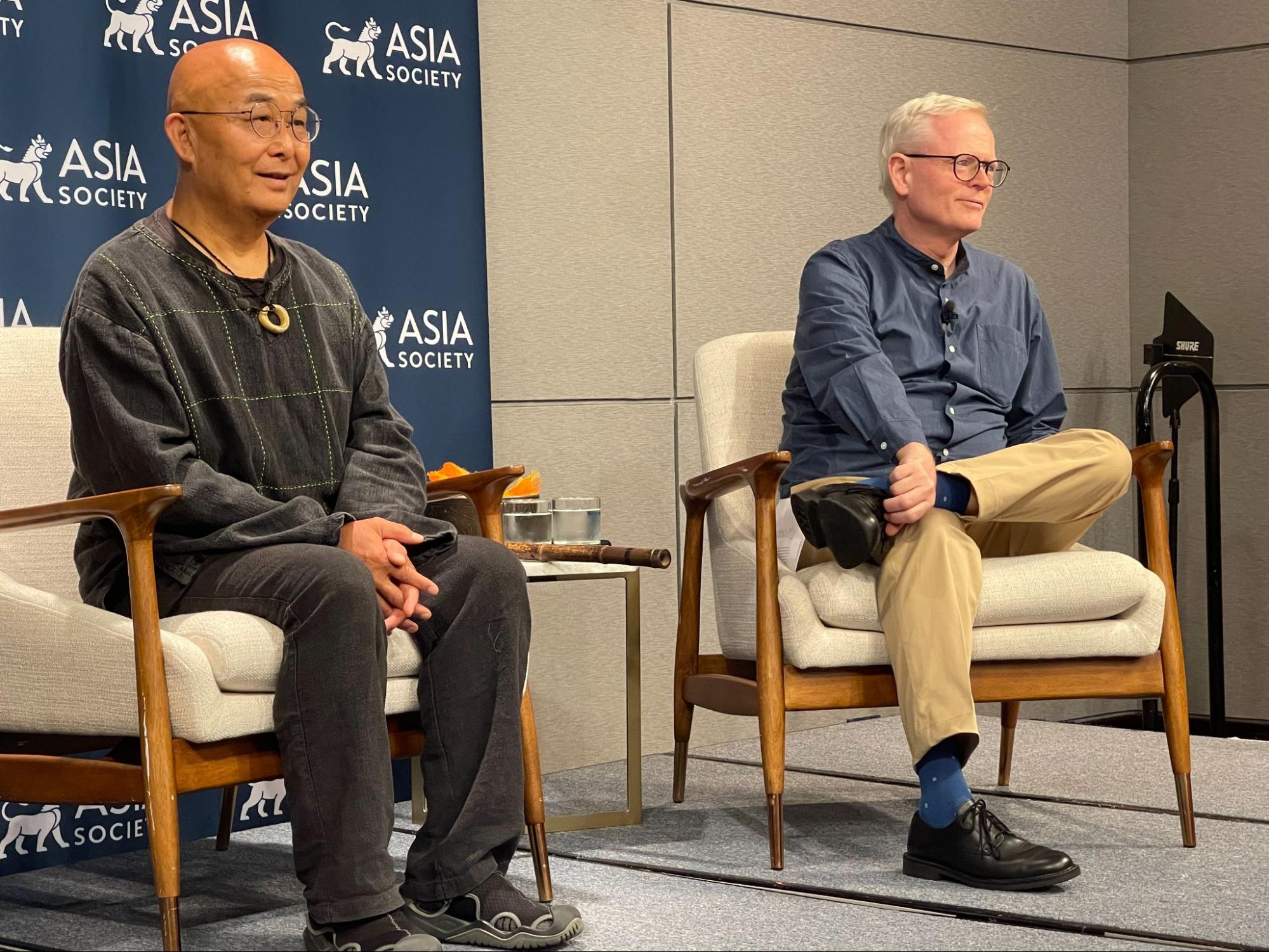

The Sichuan-born writer and street musician who spent four years in prison for “Massacre,” his poem about Tiananmen Square in 1989, talked to fellow author Ian Johnson about exile in Germany and his plan to print dictators’ faces on toilet paper.

Jonathan Landreth Published July 16, 2023

Now is not a time when many people anywhere are laughing about China. Especially not in the United States of America. Having read The Corpse Walker, exiled Chinese writer Liào Yìwǔ’s 廖亦武 real-life stories describing China from the bottom up, the last thing I expected from an audience of about 100 China-watchers gathered on Park Avenue was waves of giggles and cackles, snorts and guffaws.

After playing a somber musical opening on a long wooden flute, Liao, 64 — in the loose, faded black cotton shirt he fled persecution in, on foot, in 2011 — delighted his audience with the blunt and mischievous humor of a survivor. Unapologetic the way only humans who’ve experienced real hardship can be, Liao sat on the edge of his seat, eager to engage, even if only about half the room laughed at his Chinese jokes. The other half, this writer included, mostly relied on Vicky Wang’s smooth and nuanced translation.

The following is a condensed and edited transcript of Liao Yiwu’s conversation with Ian Johnson at the Asia Society, New York, on July 12, 2023.

— Jonathan Landreth

Ian Johnson: Tonight’s topic is exiled literature, writing in exile. And I know that the Chinese flute is very important to you because you brought it with you when you went into exile. You carried it when you walked over the border. Can you tell us a little bit about where you learn to play?

Liao Yiwu: So, during June 4, I wrote a poem that led to me being in prison for four years in four different facilities. In the last facility, I met my flute teacher, a monk. He was the oldest prisoner in the facility: 84 years old at the time. It was a cold winter’s day and I suddenly heard this crying, almost moaning sound. I asked my fellow prisoners, “What is that?” They responded, “He’s been playing every single day. How did you miss this?” So, I found my way to the monk, who was playing outside, and I stood in front of him. He played very long songs, with his eyes closed, very focused as I stood in front of him. I waited until he stopped and opened his eyes. He smiled. I smiled. He said, “Do you want to learn?” Well, that’s how I began learning how to play the flute. In prison. One thing the monk said to me in prison that I still recall very strongly: “The people outside are living in a prison without walls. We are in a prison with walls. Inside? Outside? Life isn’t that different.

Ian Johnson: Your interviews with grassroots China outsiders began when you were in prison. Before prison, you were known as a poet. When you left prison, why did you continue interviewing the kinds of people you met in prison?

Liao Yiwu: In prison, you hear unbelievable stories. At one point while I was imprisoned I was sleeping between two people on death row. One of them had murdered his wife — and he kept talking about how he had murdered his wife. He had killed her and then frozen her corpse and chopped it into pieces and cooked it. The reason that he was eventually captured was because his mother found a piece of human fingernail in her porridge. I didn’t want to listen to him, but this prisoner kept telling the same stories over and over again. One day, I finally got mad and said, “God dammit! I don’t want to hear this anymore.” And the prisoner said, “But you’re my last audience, ever. No one else is going to hear this. I will be executed, maybe tomorrow, so if I don’t tell you, who am I going to tell? After I got out of prison, I dreamed about this guy often. I decided that writing his story would be the way to get it out of my system.

When I was in prison, I shared a cell with gang members and traffickers. They all had these extraordinary stories. So that’s how I got started on the series of interviews.

Ian Johnson: This resulted in a book published in 2000 in China, Interviews with the Lower Strata of Chinese Society (中國底層訪談錄), although it was immediately banned. How did it come about? Were you very dispirited after that? Were you able to make a living?

Liao Yiwu: The banning was very unexpected. I had dreamed of a life where I wrote books like the series of interviews, one a year, making, say, 200,000 yuan [$28,000] each — rich by my region’s standards. I’d buy a house and live large. That was my dream, but then the Chinese Communist Party not only banned my book but also implicated a lot of media outlets and publishers such as Southern Weekly, all to the point where I acquired the nickname “Publisher Killer.” Anyone who published my work ended up getting shut down.

I had not anticipated any of this. In order to make a living to survive, Liú Xiǎobō 刘晓波 and Mò Shǎopíng 莫少平 of Democracy China offered me a series of columns so I could make some U.S. dollars. That was a way for me to make a living, but then the police kept harassing me and asking me about what I’m doing and what I’m writing about abroad. This made me very angry. “You, the government, have been pushing me onto the path of rebellion over and over again,” I thought.

Ian Johnson: A young journalist in Chicago was given a copy of your Chinese language interviews with grassroots China and he reached out to you. Describe how that started and what his translations meant for you.

Liao Yiwu: The young journalist in Chicago, Huáng Wén 黄文, had a Chinese friend staying with him. He asked his house guest, “Have you read any good books coming out of China lately?” The house guest said, “Yes, the series of interviews from Liao Yiwu is great and I happen to have a copy. Here you go.”

The journalist read all night and he thought it was the greatest thing. He wrote me a letter saying, “Hey, I would love to translate this book for you.” The translation went on for many years and I didn’t think much of it. Eventually, he got back in touch and said the book was getting published by Random House. I said, “Oh, okay. Published? Cool. That’s great.” And then Huang Wen asked, “Do you have any idea how much money you made? It’s about $120,000. I will send you your share of the royalties.”

So then I very excitedly purchased property in the suburbs of Chengdu in Sichuan. I thought to myself, “My god, life is so dramatic.” I never would have expected this. When I eventually left China and went into exile, obviously the property couldn’t come with me.

Ian Johnson: So, do you still own the house?

Liao Yiwu: I still have the property, but during the 2008 Sichuan earthquake the ceiling suffered some damage.

Ian Johnson: Why did you leave for Germany?

Liao Yiwu: In 2010, Germany invited me for an event and it was to be my first time traveling abroad. Many people were telling me at the time, “Once you get to Germany, you better stay.” Prior to that trip, I was denied a passport and exit visa from China over fifteen times. But 2010 was the same year that Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Nobel Prize. A Norwegian media outlet found me and asked me, “Since you’re abroad now, why don’t you come to the Nobel award ceremony?” I was the only person on Liu Xiaobo’s invitation list who was abroad and could make it. They were so enticing with their invitation. They even offered me a bottle of maotai liquor because they knew I love to drink. But I thought about it and thought, “This liquor is not worth it.” [Factcheck: Wú’ěr Kāixī 吾尔开希, former Tiananmen student leader, General Secretary, Taiwan Parliamentary Human Rights Commission, wrote to us to comment: “I was one of the dozens of Chinese dissidents who were invited and attended the Nobel Peace Prize committee ceremony, and Liao was not among us.”]

Still, I anticipated that China was moving in the right direction, that things would get better. There was Liu Xiaobo, told while in prison that he had won the Nobel Prize…“Democracy can’t be that far away,” I thought. But I also thought to myself, “Well, if I make work and am published in the U.S. and in Europe, and I earn U.S. dollars and Euros, currency-wise that really works in my favor.” At the time, the exchange rate was $1 to 8.2 yuan so I could make the USD and the Euros and live large in China and enjoy my life, all while people are thinking that I am the guy who is fighting for the cause, fighting the good fight.

So things were looking up, but then, when I returned from Germany, I was detained at the airport and asked, “What did you say in Germany? What did you do?” I ran through everything I said in Germany — nothing scandalous, nothing seditious, so I thought, “That was it. We’re okay.”

But then the next year, when the color revolution broke out in the Middle East, circumstances completely shifted. Again the police told me I was not allowed to leave the country, claiming that there was a new mandate from on high that forbade me from going abroad.

I really wanted to go, but they made it clear that if I tried again things would be very different, much more severe. “You’re gonna go missing for a while,” they said. So I was trapped in China and also wasn’t allowed to publish my prison memoir in Taiwan or in Germany. I was told that act would carry a minimum of 10 years of prison time. So, it became time to leave.

Ian Johnson: Famously, you walked across the border on foot wearing that same shirt — which has been washed since. Why Germany? Why not come to New York City?

Liao Yiwu: It was a real miracle that I got out of China at all. I carried five cell phones with me while I crossed the border on foot, all of them sturdy, original Nokias with a single contact in each. I stayed in Vietnam for three days then lived in Germany for two months. While I was in Germany, I felt like German was just too difficult a language and that Germans are kind of stiff. So, in September that year, I did come to the U.S., on September 11.

I had just published a book called God is Red. They had an African American driver pick me up holding my very red book. When I saw the man, I thought to myself, “Oh, God is black.” I did think about coming to New York, especially, as I have great aspirations for life in Flushing (Queens), because Flushing is China without the CCP. There’s no language barrier and there are plenty of undocumented people living in Flushing, so I could do exactly what I was doing in China before. Instead of interviewing Chinese people in China who were at the bottom of society, I could interview Chinese people in the U.S. I could have the same plan: do one book a year and live large. I even heard about the existence of a so-called “mistress village.”

I was very excited by this prospect, but then Germany gave me another award. This was an anti-fascism award, so that took me back to Germany. I stayed a while and then went to the U.S. again. But then Germany gave me an artist-in-residence program and the conditions were just wonderful. I had a 2,500 Euro [$2,800] monthly stipend. They gave me a huge apartment. At the time, a journalist asked me, “So? What do you think of this program?” I replied, “Even the greatest poets in China, like Lǐ Bái 李白 and Dù Fǔ 杜甫, never lived as well as I’m living now. This is crazy.”

Ian Johnson: One of the problems that exiled writers often have is making a living. In Germany, you were quite lucky with the publisher Fischer, which has quite an anti-fascist history since its founding after World War II. They gave you book contracts and have supported you over the years. Talk a little bit about what it’s generally like for exiled writers.

Liao Yiwu: Fischer is one of the oldest publishing houses in Germany, established in 1886. I feel very lucky to have been published by them all these years. Eleven books so far and two more on the way. Another blessing is the fact that I found a wonderful German translator to collaborate with, Peter Hoffmann. When we first met, Peter was holding a guitar, looking like a poet, and singing “Nothing to my Name,” (一无所有) Cui Jian’s anthem of the protests of 1989.

I stopped myself like, “What? Who is this? What is this?” Then Peter the translator asked me, “So, are we going to have a drink?” That’s when I knew he was my translator. Now he is a very established and well-known professor at a great university in Germany. He is known as my German face.

Still, my biggest marketer, my biggest promoter, is Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 . At one point, a Chinese Ambassador in Germany came to me and said, “Look, if you keep this up, there’s going to be trouble for your family back home. It’s going to be an issue.”

I replied: “I have published so many books abroad that if you keep harassing me, if you keep this up, you might as well go build me a bank. Every time you do something to me now, it’s an international incident with news headlines everywhere.” At this point, I’m a little embarrassed about this. Obviously, the ambassador didn’t take this well.

I was very excited to find out that Xi Jinping had published 128 books himself. Anytime he does anything, it just makes the Western world pay even more attention. For example, consider what happened in Wuhan. The leadership’s approach to disease control and to surveillance makes the world very curious about Xi Jinping, about China. And the first point of reference, their best point of reference is Liao Yiwu. So, anytime something happens with Xi Jinping, mine is the book they buy. One of my most recent books, Wuhan, has been selling really well in Germany. Even I can’t believe this is happening.

Ian Johnson: You’re so well-received in Germany. I lived in Berlin for quite a while and I went over to your house for dinner, and you said, “Oh, Herta Müller is coming by.” She’s the Nobel Literature Prize-winning Romanian-German author. She lives nearby and goes to your house every few months for dinner. You also said, “Wolf Biermann is coming for dinner.” He’s the Bob Dylan of Germany. After Liu Xiaobo died, you were able to use some of these connections, including the former Lutheran pastor Joachim Gauck, who was the head of the Stasi Archives, and later became President of Germany, to work to get [Liu Xiaobo’s widow] Liú Xiá 刘霞 a real shot at being released to Germany. Please talk about that process and an exiled writer’s responsibility to stay politically active.

Liao Yiwu: Before Liu Xiaobo got sick, there was already a plan put in motion. They were trying to convince his wife to leave China. This was largely orchestrated by Wolf Biermann, the famous poet, because he felt like there was really no point in staying in China when the Communist Party was behaving the way it was. He wrote to Liu Xia himself and persuaded her to apply to leave the country and convince Liu Xiaobo to do the same. This was the first time we understood what his wife had been going through, suffering from depression. There were many meetings to make this happen, and through all this, Wolf Biermann is talking with Angela Merkel, the Chancellor of Germany at the time. She was a fan of his in her youth, so they have a special relationship. They’re in very close contact. When they found out Liu Xiaobo had cancer, they held a summit in Hamburg. Wolf Biermann was calling nonstop. It didn’t matter if Merkel was talking to Trump or talking to Xi Jinping, Biermann was calling her about the rescue.

Eventually, Xi Jinping said, “We’ll look into it,” but nothing came of it. Unfortunately, Xiaobo passed away. Now the rescue was for Liu’s widow. He believed that it was part of his self-fulfillment, because of his background, his history in East Germany living under communist surveillance. He felt very passionately about this cause. If Liu Xia could leave China, it would be because of Wolf Biermann who’d written many letters and made many calls on her behalf.

Ian Johnson: And she did, in October 2018. These are some of the things you can do when you’re in exile, but do you feel cut off from China, especially as somebody who has done so many grassroots interviews?

Liao Yiwu: Actually, I have always wanted to be disconnected from China. I identify much more strongly as a Sichuan person, a person who likes his liquor and has a lot of bad habits commonly associated with being from Sichuan. I gave a speech years ago saying that I feel like China, as an Empire, must fracture. That would be the ideal outcome for me. If China fractured into multiple pieces, I’d only have to go as far as Yunnan to be an exile, not as far as Germany. Taiwan is also too far. Anyway, no Sichuan person has ever felt very strongly about unification.

My ideal outcome would be for Sichuan to elect a president who’s either an alcoholic or a chef or both. Instead of a Chinese-style democracy there could be a Sichuan-style democracy and Ian Johnson, if he ever wants to, can come for a visit. He could just come to Liao Yiwu for a visa. This would be the most ideal outcome.

I’ve always wanted to make that distinction. I’ve lived in China for over 50 years of my life, but I have a lifetime of material. There’s a New York Times reporter in the back of the room who’s asked me before. “Are you going to run out of material because you’re disconnected from China?” No, I write all the time. I boasted to him that I have 30 to 50 more books in me. I can write until my arm falls off and I’ll still have plenty of material.

Ian Johnson: Why don’t we move to audience questions?

Audience member 1: Everyone in our high school read your book The Corpse Walker for one of our classes. We had a very strong memory of reading it. In that book you did a lot of interviews with different people from a lot of backgrounds. What was it like talking to them? Where did you find these people? How did you know them and what was the process of interviewing them?

Liao Yiwu: The interviewees came from my prison time. I didn’t have to look for them. After I got out of prison, no one wanted to hire me and so, to make a living, I was playing the flute at bars late at night, at three or four in the morning. By 4 a.m., the only people who are at the bar are either depressed, brokenhearted, or homeless. Initially, I would play for free, playing these very sad melodies. I’d go up to these guys and play in front of them.

“Don’t worry, it’s free,” I’d say.

They’d say, “Okay, fine.”

But eventually they’d say, “Wait. No. Don’t stop. Please keep playing.”

And then I’d tell them, “Well, it used to be 10 yuan [$1.40) , now it’s 50,” and I’d continue playing.

These people I ended up interviewing would be so moved by the music they’d be crying and just spilling their life stories by the end of it. The next morning, I’d get home and be so tired I’d sleep most of the day and not go back to work. That made enough money to get through the day. So, 50 yuan times five, that was enough to get through.

By day three, I’d run out of money and then go back to the bar. The bar owner told me I had a terrible work ethic. That was the cycle of my routine of interviewing people. I have over 300 interviews in my archives, deep in my computer. I’ll be dragging them out as far as long as I’m alive. And after I’m dead, Ian Johnson will inherit them and see what he can do with my interview material.

Audience member 2: Thank you very much. I don’t speak your beautiful language, but I want to know how you feel about living in Berlin today and do you plan to stay?

Liao Yiwu: So, aside from my hometown Chengdu, Berlin is the city I know the best. I’m a person with no sense of direction, so I’m not familiar with a lot of cities. What I really like to do is visit the huge graveyard near my place in Berlin. I like to go there because dead people don’t talk back — and if they’re not talking back, they’re essentially agreeing with you. These graveyards tend to be quite lovely. There are a bunch of birds and so I go and talk to the headstones and have a very refreshing day with very good conversations. You don’t need to learn English or German to converse with the dead. Another thing I like to do is imagine the people buried there are my readers. This enables me to have a conversation, to communicate with my readers. This is very comfortable. In many ways I believe Berlin is even better than my hometown Chengdu.

Audience member 3: Could you comment on how the power of the Communist Party is growing and how technology has enabled it to reach further and more precisely. What might this mean for future dissident voices? Will they be silenced?

Liao Yiwu: In China right now, the surveillance that began in Xinjiang with 12 million Uyghurs has since spread like a virus to the whole. The surveillance has become nationwide. It’s very high tech and, at this point, it’s even being pushed abroad internationally with programs like WeChat. On the other side of this is the idiot leader at the top. Xi Jinping is someone who would carry a bushel of barley on his shoulders for five kilometers and not change shoulders. So it could be any day that he could just fall on his face. You never know. China right now is quite a perverse society in the sense that it has an idiotic ruler but, at the same time, incredibly severe control. So there are two very severe extremes.

In this environment, a writer is incredibly useful. A writer is someone who is observing and keeping records of everything that’s happening because the average person may not even notice. We’re just going to wait for the day when China fractures into multiple countries, and then we will hire Ian Johnson to come and rule the country.

Audience member 3: Thank you very much for making some very heavy things lighter with your humor. We’ve talked a lot about China. I know you haven’t lived in the United States for long periods of time, but I’m interested in your perception of the United States at a time when we are very concerned about the state of democracy in our country. I wonder if you have any advice for us?

Liao Yiwu: This question should be addressed to Ian Johnson, not me.

Ian Johnson: Maybe you don’t have an opinion?

Liao Yiwu: This is too big a question to handle without liquor.

Audience member 4: You predicted twenty years ago some fracturing of China as a nation. Based on the colonization of Xinjiang and the circumstances happening in Sichuan, would you be interested in writing a book specifically about the society and history of Sichuan?

Liao Yiwu: I’m the only one who has actually thought about this for a very long time.

I would like to open a factory that manufactures toilet paper paper rolls. On the toilet paper rolls we would print every dictator’s face, so we can think about them often. Especially those with hemorrhoids. So we could have Xi Jinping, we could have Putin, we could have Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 , we could have Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平, and many other dictators. Each would be a big roll. Lots of sheets. We could think about these dictators often, when we wipe our butts, and see how many of them we can recognize. If I patent this idea, I’ll be rich and won’t have to worry about writing books anymore.

Audience member 5: I thank you so much for the conversation today. I was wondering if now you have connections with young people in China and, if so, what is your perception about how they feel politically? What is the energy among young people? How do they feel about their leadership in the country and the direction of the country?

Liao Yiwu: Previously, I actually didn’t really have a lot of contact with young Chinese people, especially the Chinese international students who are in Germany who would prefer not to associate with me for safety reasons, because they still want to go back to China.

But then, last year, there was the A4 Revolution, or the White Paper Revolution, the anti-zero-COVID revolution. When that happened, I was giving a talk in Stuttgart about the revolution and the reaction. There were a lot of students who were there protesting with blank white paper. One of the student leaders approached me and we had a great conversation. Without reservation, I admit that I had previously underestimated the youth, and now I recognize that they have their way and their wisdom in how they approach a revolution. That conversation, with about a dozen Chinese students in Germany, well over an hour long, was one of the most fruitful conversations that I’ve had since leaving China.

Jonathan Landreth is a Brooklyn-based writer and editor who started reporting from China in 1997. Read more

作家廖亦武:白痴习近平是“我最大的推销商”

这位出生于四川的作家兼街头音乐家,曾因创作关于1989年天安门广场的诗歌《大屠杀》而被判入狱四年,他与同行作家伊恩·约翰逊谈论了流亡德国的经历以及他在厕纸上印上独裁者头像的计划。

廖亦武有时被称为“四川的突厥人”,因为他口述了中国社会最底层的普通人的历史。7 月 12 日,他在纽约亚洲协会的演讲引得观众捧腹大笑。作家伊恩·约翰逊在中参馆和美国笔会联合主办的活动中采访了廖亦武。照片:乔纳森·兰德雷斯。

2023 年 7 月 16 日

纪录整理者乔纳森·兰德雷斯 (Jonathan Landreth)是布鲁克林的一位作家兼编辑,他从 1997 年开始在中国从事报道工作。

现在不是很多人嘲笑中国的时候。尤其在美国。读过《行尸走肉》 ——流亡中国作家廖亦武从底层描述中国的真实故事——之后,我最没想到的是,在公园大道上聚集的约 100 名中国观察家会发出阵阵咯咯笑声、嗤之以鼻声和哄堂大笑声。

廖亦武用长木笛吹奏了一段忧郁的开场曲,64 岁的廖亦武身穿宽松褪色的黑色棉质衬衫,2011 年他徒步逃离迫害时就穿着这件衬衫,用幸存者直率而调皮的幽默逗乐了观众。廖亦武坐在座位边上,毫无歉意,只有经历过真正苦难的人才会这样,他渴望与观众互动,即使只有大约一半的观众对他的中文笑话发笑。另一半观众,包括本文作者,主要依靠 Vicky Wang 流畅而细致的翻译。

以下是廖亦武 2023 年 7 月 12 日在纽约亚洲协会与伊恩·约翰逊对话的精简和编辑记录。

— 乔纳森·兰德雷斯

伊恩·约翰逊:今晚的主题是流亡文学、流亡写作。我知道中国笛子对你来说非常重要,因为你流亡时带着它。你走过边境时也带着它。你能告诉我们你在哪里学笛子吗?

廖亦武:六四那年,我写了一首诗,这首诗让我在四个不同的监狱里待了四年。在最后一个监狱里,我遇到了我的笛子老师,一个僧人。他是监狱里最年长的囚犯:当时 84 岁。那是一个寒冷的冬日,我突然听到一种哭喊声,几乎是呻吟声。我问我的狱友:“那是什么?”他们回答说:“他每天都在吹笛子。你怎么会错过这个?”于是,我找到了正在外面吹笛子的僧人,我站在他面前。他吹了很长的曲子,闭着眼睛,非常专注,我站在他面前。我一直等到他停下来睁开眼睛。他笑了。我也笑了。他说:“你想学吗?”就这样,我开始学习吹笛子了。在监狱里。僧人在监狱里对我说的一句话让我至今记忆犹新:“外面的人生活在没有围墙的监狱里。我们生活在有围墙的监狱里。室内?室外?生活并没有什么不同。

伊恩·约翰逊:你对中国草根阶层的采访始于入狱期间。入狱前,你以诗人闻名。为什么出狱后,你仍继续采访你在监狱里遇到的那些人呢?

廖亦武:在监狱里,你会听到令人难以置信的故事。有一次,我在两个死刑犯中间睡觉。其中一个人谋杀了他的妻子——他一直在说他是如何谋杀妻子的。他杀了她,然后冷冻尸体,将其切成碎片煮熟。他最终被捕的原因是他的母亲在粥里发现了一块指甲。我不想听他讲,但这个囚犯一遍又一遍地讲着同样的故事。有一天,我终于生气了,说:“该死的!我不想再听这些了。”囚犯说:“但你是我最后一次听众了。没有人会听到这些。我明天就会被处决,如果我不告诉你,我要告诉谁呢?”出狱后,我经常梦到这个家伙。我决定写他的故事来发泄我的愤怒。

我在监狱里和帮派成员、人贩子关在一间牢房里。他们都有这些不寻常的故事。这就是我开始这一系列采访的原因。

伊恩·约翰逊:这导致了 2000 年在中国出版了一本书,《中国社会底层访谈录》,尽管这本书很快就被禁了。这本书是怎么诞生的?之后你很沮丧吗?你能以此谋生吗?

廖亦武:这次被禁非常出乎意料。我曾梦想过这样的生活:每年写一本这样的采访系列书,每本能赚 20 万元人民币(28,000 美元)——以我们当地的标准来看,这已经很富裕了。我会买房,过上奢侈的生活。那是我的梦想,但后来中共不仅禁了我的书,还牵连了很多媒体和出版商,比如《南方周末》,以至于我得到了“出版商杀手”的绰号。所有发表我作品的人最终都被封了。

这一切我都没想到。为了生存,民主中国的刘晓波和莫少平给我提供了一系列专栏文章,让我可以赚一些美元。那是我谋生的手段,但后来警察一直骚扰我,问我在国外做什么、写什么。这让我很生气。“你们政府一次又一次地把我推上反叛的道路。”我想。

伊恩·约翰逊:芝加哥的一位年轻记者收到了您翻译的中文版中国基层采访稿,他联系了您。您能描述一下这件事的起因吗?他的翻译对您来说意味着什么?

廖亦武:芝加哥的年轻记者黄文有一位中国朋友住在他家。他问这位朋友:“你最近读过什么中国出的好书吗?”这位朋友说:“读过,廖亦武的系列采访写得很棒,我正好有一本。给你。”

这位记者通宵阅读,他认为这是最棒的事情。他给我写了一封信,说:“嘿,我很乐意为你翻译这本书。”翻译工作持续了很多年,我对此并不怎么在意。最后,他再次联系我,说这本书将由兰登书屋出版。我说:“哦,好的。出版了?太棒了。太好了。”然后黄文问道:“你知道你赚了多少钱吗?大约 12 万美元。我会把你的那份版税寄给你。”

于是我兴奋地在四川成都郊区买了一套房子。我心想:“天哪,生活真是戏剧化。”我从来没有想到过这一点。当我最终离开中国,流亡海外时,这套房子显然不能随我而去。

伊恩·约翰逊:那么,这所房子还属于你吗?

廖亦武:这个房子我还保留着,但是2008年四川地震的时候天花板有些损坏。

伊恩·约翰逊:您为什么要去德国?

廖亦武: 2010年,德国邀请我参加一个活动,那是我第一次出国。当时很多人跟我说,“到了德国,就留下来吧”。在那之前,我被中国拒发护照和出境签证十五次之多。但2010年,正是刘晓波获得诺贝尔奖的一年。一家挪威媒体找到我,问我,“既然你现在在国外,为什么不来参加诺贝尔颁奖典礼?”我是刘晓波邀请名单上唯一一个在国外的人,能来参加颁奖典礼。他们的邀请很有诱惑力,他们还送了我一瓶茅台酒,因为他们知道我喜欢喝酒。但我想想,“这点酒不值得。” [事实核查:前天安门学生领袖、台湾议会人权委员会秘书长吾尔开希写信给我们评论道:“我是受邀参加诺贝尔和平奖委员会颁奖典礼的数十名中国异见人士之一,而廖亦武不在我们之中。”]

尽管如此,我还是预计中国正朝着正确的方向发展,情况会越来越好。刘晓波在狱中被告知他获得了诺贝尔奖……“民主离我们并不遥远”,我想。但我也想,“好吧,如果我创作作品并在美国和欧洲出版,我就能赚到美元和欧元,从货币角度来看,这对我来说确实很有利。”当时的汇率是 1 美元兑 8.2 元人民币,所以我可以赚到美元和欧元,在中国过上奢侈的生活,享受生活,而人们却认为我是为事业而奋斗、为正义而战的人。

事情开始有了好转,但后来,当我从德国回来时,我在机场被扣留了,他们问我:“你在德国说了什么?你做了什么?”我把我在德国说的每一句话都说了一遍——没有丑闻,也没有煽动性的话,所以我想,“就这样吧。我们没事了。”

但第二年,中东爆发了颜色革命,情况完全变了。警察又一次告诉我,不准我出国,说是上级下达了新命令,不准我出国。

我真的很想去,但他们明确表示,如果我再次尝试,情况将大不相同,会严重得多。“你会失踪一段时间,”他们说。所以我被困在中国,而且不允许在台湾或德国出版我的狱中回忆录。我被告知,这项法案至少会判处 10 年监禁。所以,是时候离开了。

伊恩·约翰逊:众所周知,你曾穿着那件衬衫徒步穿越边境——那件衬衫后来被洗掉了。为什么是德国?为什么不来纽约呢?

廖亦武:我能走出中国真是个奇迹。我徒步过境时带了五部手机,都是诺基亚原装的,很结实,每部手机只有一个联系人。我在越南呆了三天,然后在德国住了两个月。在德国的时候,我觉得德语太难了,德国人有点呆板。所以,那年九月,我终于到了美国,9月11日。

当时我刚刚出版了一本名为《上帝是红色》的书。他们派了一位非裔美国司机来接我,手里拿着我的那本红色的书。当我看到那个男人时,我心想:“哦,上帝是黑人。”我确实想过来纽约,尤其是因为我非常向往法拉盛的生活,因为法拉盛是没有中共的中国。这里没有语言障碍,而且有很多无证移民生活在法拉盛,所以我可以做我以前在中国所做的事情。我可以采访美国的中国人,而不是采访中国社会最底层的中国人。我可以有同样的计划:每年写一本书,过上奢侈的生活。我甚至听说过所谓的“二奶村”的存在。

我对这个前景感到非常兴奋,但后来德国又给了我一个奖项。这是一项反法西斯奖,所以我又回到了德国。我待了一段时间,然后又去了美国。但后来德国给了我一个艺术家驻留计划,条件非常好。我每月有 2,500 欧元(2,800 美元)的津贴。他们给了我一套大公寓。当时,一位记者问我:“那么?你觉得这个项目怎么样?”我回答说:“即使是中国最伟大的诗人,比如李白和杜甫,也没有像我现在这样生活得这么好。这太疯狂了。”

伊恩·约翰逊:流亡作家经常遇到的一个问题就是谋生。在德国,你很幸运,因为有菲舍尔出版社,这家出版社自二战后成立以来,一直致力于反法西斯主义。他们与你签订了图书合同,多年来一直支持你。谈谈流亡作家的一般生活吧。

廖亦武:菲舍尔出版社是德国最古老的出版社之一,成立于 1886 年。这些年来,我很幸运能和他们合作出版书籍。目前为止,我已经出版了 11 本书,还有两本即将出版。另一件幸运的事是,我找到了一位出色的德语翻译彼得·霍夫曼来合作。我们第一次见面时,彼得拿着一把吉他,像个诗人一样,唱着崔健为 1989 年抗议活动创作的歌曲《一无所有》。

我停住了,想:“什么?这是谁?这是什么?”然后翻译彼得问我:“那么,我们要喝一杯吗?”那时我才知道他是我的翻译。现在他是德国一所著名大学的资深知名教授。他被称为我的德国面孔。

不过,我最大的营销者、最大的推动者是习近平。有一次,一位中国驻德国大使来找我,对我说:“你看,如果你继续这样下去,你国内的家人会遇到麻烦。这会成为一个问题。”

我回答说:“我在国外出版了这么多书,如果你继续骚扰我,如果你继续这样,你还不如去给我建一家银行。现在你每次对我做什么,都是国际事件,到处都是新闻头条。”说到这里,我有点尴尬。显然,大使对此并不满意。

我很高兴得知习近平自己已经出版了 128 本书。每当他做任何事情,都会让西方世界更加关注。例如,想想武汉发生的事情。领导层对疾病控制和监控的态度让世界对习近平和中国非常好奇。他们的第一个参考点,最好的参考点就是廖亦武。所以,每当习近平有什么事情发生,他们就会买我的书。我最近的一本书《武汉》在德国卖得很好。连我都不敢相信这是真的。

伊恩·约翰逊:您在德国很受欢迎。我在柏林住了很长一段时间,有一次我去您家吃饭,您说:“哦,赫塔·穆勒要来。”她是诺贝尔文学奖得主、罗马尼亚裔德国作家。她住在附近,每隔几个月就去您家吃饭。您还说:“沃尔夫·比尔曼要来吃饭。”他是德国的鲍勃·迪伦。刘晓波去世后,您利用了一些关系,包括前路德教会牧师约阿希姆·高克(Joachim Gauck),他曾担任史塔西档案馆馆长,后来成为德国总统,努力让刘霞有机会获释回德国。请谈谈这个过程以及流亡作家保持政治活跃的责任。

廖亦武:在刘晓波患病之前,就已经有一个计划在实施。他们试图说服他的妻子离开中国。这主要是著名诗人沃尔夫·比尔曼一手策划的,因为他觉得在共产党如此行事的情况下,留在中国真的没有意义。他亲自写信给刘霞,说服她申请离开中国,并说服刘晓波也这么做。这是我们第一次了解他的妻子患有抑郁症,经历了什么。为了实现这一目标,他们开了很多次会议,在这期间,沃尔夫·比尔曼与当时的德国总理安格拉·默克尔进行了交谈。默克尔年轻时是沃尔夫·比尔曼的粉丝,所以他们关系很特别。他们联系很密切。当他们得知刘晓波患癌时,他们在汉堡举行了一次峰会。沃尔夫·比尔曼不停地打电话。不管默克尔是在和特朗普谈话,还是在和习近平谈话,比尔曼都在给她打电话,讨论救援事宜。

最后,习近平说:“我们会调查此事”,但最终没有结果。不幸的是,晓波去世了。现在的营救对象是刘霞的遗孀。他相信这是他自我实现的一部分,因为他的背景,他在东德曾生活在共产党的监视之下。他对这项事业充满热情。如果刘霞能够离开中国,那将是因为沃尔夫·比尔曼为她写了很多信,打了很多电话。

伊恩·约翰逊:她确实在 2018 年 10 月回来了。这些都是你在流亡期间可以做的事情,但你是否感觉与中国隔绝了,尤其是作为一个做过这么多基层采访的人?

廖亦武:其实我一直都想脱离中国。我更强烈地认为自己是四川人,喜欢喝酒,有很多四川人特有的坏习惯。几年前我发表过演讲,说我觉得中国作为一个帝国,必须分裂。这对我来说是最理想的结果。如果中国分裂成多个部分,我只要去云南就可以流亡,而不用去德国。台湾也太远了。无论如何,没有一个四川人对统一有强烈的感觉。

我最理想的结果是四川选出一个要么是酒鬼要么是厨师或者两者兼而有之的总统。中国式民主可以改为四川式民主,伊恩·约翰逊如果愿意的话可以来访问。他可以来辽宁省办签证。这将是最理想的结果。

我一直想做这样的区分。我在中国生活了 50 多年,但我有一生的写作素材。房间后面有一位《纽约时报》记者曾经问过我:“你会因为与中国断绝联系而写不出素材吗?”不会,我一直在写作。我向他夸耀我还能写出 30 到 50 本书。我可以一直写到手臂断掉,而且我还会有很多素材。

伊恩·约翰逊:我们何不开始回答观众的问题呢?

观众 1:我们高中的每个人都在课堂上读过您的书《行尸走肉》。我们对这本书记忆犹新。在那本书中,您采访了来自不同背景的不同人。与他们交谈感觉如何?您在哪里找到这些人的?您是如何认识他们的?采访他们的过程是怎样的?

廖亦武:采访对象都是我坐牢时拍的,我没找他们。出狱后,没人愿意雇我,为了生活,我就在酒吧里吹笛子,晚上三四点才去。到凌晨四点,酒吧里只有抑郁症患者、失恋者或无家可归者。一开始,我都是免费演奏,吹一些非常悲伤的旋律,走到他们面前,在他们面前吹。

“别担心,它是免费的,”我会说。

他们会说,“好的,没问题。”

但最终他们会说:“等一下。不。别停下来。请继续玩。”

然后我会告诉他们,“嗯,以前是10元(1.4美元),现在是50元”,然后我会继续玩。

我采访的这些人会被音乐深深打动,他们会哭着讲述自己的人生故事。第二天早上,我回到家,会非常疲惫,会睡上大半天,不会再去上班。这样赚的钱足够我度过一天。所以,50 元乘以 5,就足够我度过一天了。

到第三天,我的钱就花光了,然后我又回到酒吧。酒吧老板说我工作态度很差。这就是我采访别人的日常周期。我的档案里有 300 多个采访记录,都藏在电脑深处。只要我还活着,我就会一直把它们拿出来。我死后,伊恩·约翰逊会继承这些记录,看看他能用我的采访材料做些什么。

观众 2:非常感谢。我不懂您那优美的语言,但我想知道您现在住在柏林的感受如何,您打算留下来吗?

廖亦武:除了我的家乡成都,柏林是我最熟悉的城市。我是一个没有方向感的人,所以对很多城市都不熟悉。我真正喜欢做的是参观柏林我家附近的大型墓地。我喜欢去那里,因为死人不会顶嘴——如果他们不顶嘴,他们实际上是在同意你的话。这些墓地往往非常可爱。那里有很多鸟,所以我会去和墓碑聊天,度过非常愉快的一天,进行非常愉快的交谈。你不需要学习英语或德语就可以与死者交谈。我喜欢做的另一件事是想象埋葬在那里的人是我的读者。这使我能够与读者交谈,交流。这很舒服。在很多方面,我认为柏林甚至比我的家乡成都更好。

观众 3:您能否评论一下共产党的权力如何不断增长,以及技术如何使其影响力更广、更精准。这对未来异见人士的声音意味着什么?他们会被压制吗?

廖亦武:在中国,监控始于新疆,监控 1200 万维吾尔人,现在像病毒一样蔓延到整个中国。监控已经扩展到全国。监控技术非常先进,目前甚至通过微信等程序在国际上推广。另一方面,最高领导人是白痴。习近平是那种可以扛着一蒲式耳大麦走五公里而不换肩膀的人。所以他随时都有可能摔个跟头。你永远不知道。中国现在是一个相当反常的社会,一方面它有一个白痴统治者,另一方面又有极其严厉的控制。所以有两个非常严厉的极端。

在这种环境下,作家非常有用。作家就是观察和记录正在发生的一切的人,因为普通人可能根本注意不到。我们只是要等到中国分裂成多个国家的那一天,然后我们就会雇佣伊恩·约翰逊来统治这个国家。

观众 3:非常感谢您用幽默让一些非常沉重的话题变得轻松起来。我们谈论了很多关于中国的事情。我知道您在美国居住的时间不长,但我感兴趣的是,在我们非常担心我国民主状况的时候,您对美国的看法。我想知道您有什么建议给我们吗?

廖亦武:这个问题应该问伊恩约翰逊,不是我。

伊恩约翰逊:也许你没有意见?

廖亦武:这个问题太大了,没有酒是解决不了的。

观众 4:二十年前您就预言中国会分裂。根据新疆的殖民统治和四川的情况,您是否有兴趣专门写一本关于四川社会和历史的书?

廖亦武:其实只有我一个人考虑这个问题很久了。

我想开一家生产卫生纸卷筒的工厂。在卫生纸卷筒上印上每个独裁者的脸,这样我们就可以经常想起他们。特别是那些有痔疮的人。这样我们就可以有习近平、普京、毛泽东、邓小平和其他许多独裁者的脸。每个都是一大卷。很多张纸。我们可以经常在擦屁股的时候想起这些独裁者,看看我们能认出他们中的多少人。如果我为这个想法申请了专利,我就会发财,再也不用担心写书了。

观众 5:非常感谢您今天的访谈。我想知道您现在是否与中国的年轻人有联系,如果有,您如何看待他们的政治观?年轻人的活力如何?他们如何看待自己在国家中的领导力和国家的发展方向?

廖亦武:以前我其实跟中国的年轻人接触不多,特别是在德国的中国留学生,他们因为安全考虑,都不愿意跟我交往,因为他们还想回中国。

但去年发生了 A4 革命,又称白皮书革命,即反零新冠革命。那次革命发生时,我在斯图加特就这场革命及其反应发表演讲。当时有很多学生拿着白纸抗议。一位学生领袖走近我,我们进行了一次愉快的交谈。我毫无保留地承认,我以前低估了年轻人,现在我意识到他们在革命方面有自己的方式和智慧。那次谈话持续了一个多小时,我与十几名在德国的中国学生进行了交谈,这是我离开中国以来最富有成效的谈话之一。

乔纳森·兰德雷斯 (Jonathan Landreth)是布鲁克林的一位作家兼编辑,他从 1997 年开始在中国从事报道工作。